Treatment and Management

Contents

Treatment and Management

There is no consensus on the best way to treat or manage ICP. Many hospitals have adopted a policy of ‘active management’ with ICP pregnancies in anticipation that this approach might reduce any risk to the unborn baby. The term ‘active management’ is used to describe various strategies that hospitals use to monitor your ICP pregnancy, and may include some or all of the following:

-

Your doctor should monitor your non-fasting bile acid concentrations and liver enzyme levels through blood tests. These tests are often performed weekly, but the frequency may depend on how many weeks pregnant you are. We recommend testing twice a week from 33-34 weeks of pregnancy as the bile acids can suddenly rise.

Athough the itch is not thought to be directly linked to the level of bile acids, if your itching suddenly becomes worse it is reasonable to request that your blood is tested. This is particularly important because bile acid concentrations ≥40 µmol/L are associated with an increased risk of spontaneous preterm labour and potential admission of the baby to the neonatal unit, and bile acid concentrations of ≥100 µmol/L are associated with stillbirth.Blood tests are described in more detail in Diagnosis.

-

Your doctor may want to monitor your baby.

You may be asked to have CTG (cardiotocography) monitoring to check on your baby’s heartbeat, but there is no research to suggest that CTGs (or non-stress tests) are able to predict which babies are at risk of complications associated with ICP. While they may feel reassuring to have, they should not be relied on as confirmation that all is well with the unborn baby. This is because they cannot detect the very subtle changes (called arrhythmia) thought to be caused by high bile acids and it is therefore important that women and birthing people continue to monitor their baby’s pattern of movements at all times.

You may also be asked to have additional ultrasound scans of your baby – this is usually to check on your baby’s well-being and/or growth. There is no evidence to suggest that ICP can affect the growth of your baby, and most experts on ICP do not suggest extra scans as routine in the management of ICP unless there are other medical reasons to be doing so (for example if it has been noted that you have a smaller then average baby). There is also no evidence to suggest that using ultrasound scans to check your baby’s well-being can pick up any potential problems.

Equally as important, you can be your own monitor of your baby’s movements and report any changes that you notice. This is something that applies to all pregnant women, and you should immediately contact your hospital if your baby’s movements change, slow down or stop.

-

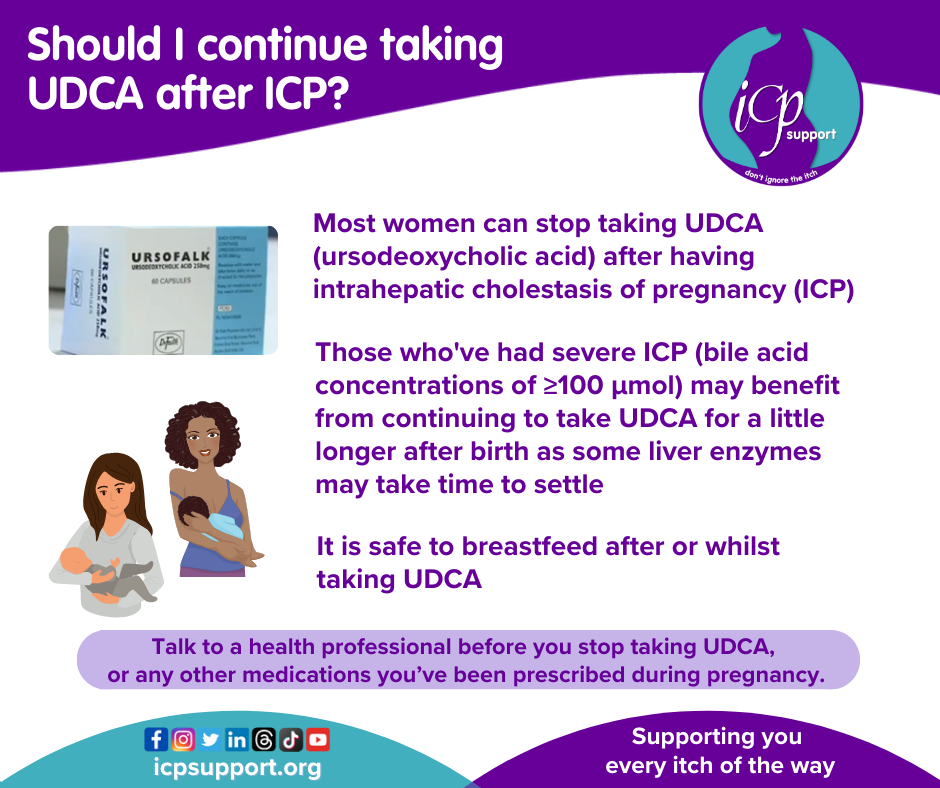

The most commonly used treatment in ICP is a drug called ursodeoxycholic acid (also known as urso, UDCA, Actigall and ursodiol). You can find more information here.

-

Because we know that UDCA doesn’t reduce bile acid levels or improve itch for all women, other medications have been tried for those women who don’t respond to it.

Rifampicin has been introduced in recent years as an additional medication to take in conjunction with UDCA for those women with severe ICP and who are not responding to UDCA alone. Because it can worsen liver blood tests it should be prescribed in consultation with a doctor who has specialist knowledge of using it in ICP. Rifampicin is an antibiotic which is most commonly used in the treatment of tuberculosis (TB), including the treatment of TB in pregnant women. It has been used to treat several other cholestatic liver diseases, including primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC), where it has been shown to be effective at improving some of the enzymes in liver blood tests and reducing bile acid levels. It also improves itch in people with PBC. A recent research paper has suggested that it can help some women with very severe ICP, but further studies are needed to establish how effective it is as a treatment for the condition. The main side-effect of rifampicin treatment is that it colours your body fluids (urine, tears etc.) orange/red.

A new trial, called TURRIFIC, is currently under way in Australia, Sweden, Finland and the UK to evaluate its efficacy. ICP Support is a collaborator on this study.

Dexamethasone is a steroid that has previously been used to improve the symptoms of ICP by reducing the production of hormones. However, prolonged exposure to steroids during pregnancy is now considered to be harmful, and dexamethasone is no longer used to treat ICP. You may, however, be offered injections of dexamethasone or another steroid (betamethasone) if your doctors are considering delivering your baby early. This will help your baby’s lungs to mature and prepare them for birth. Some women report that their itching temporarily improves after having these injections.

Chlorpheniramine (also known as piriton) is an antihistamine that is sometimes prescribed because some doctors hope that it will reduce the sensation of itch, but there is no evidence that this is the case. However, it may also have the side-effect of making you feel drowsy, therefore helping you to sleep. It has no effect on the enzymes in your liver blood test and does not reduce bile acid levels.

Vitamin K supplements may be used if you have steatorrhoea. Some women with ICP may have problems in absorbing fat. If this is happening to you, you will notice that your stools become pale. In addition to this, if you are not absorbing fat you will not be absorbing Vitamin K (because it’s a fat-soluble vitamin). Vitamin K helps your blood to clot, so if you do not absorb it properly you may have an increased risk of bleeding heavily after the birth of your baby (post-partum haemorrhage). To try to reduce this risk, some women are offered oral vitamin K (the water-soluble form). However, post-partum haemorrhage in ICP is relatively uncommon and there is no research to show that prescribing vitamin K actually does reduce the risk of bleeding. Vitamin K treatment will have no effect on your symptoms, liver blood test results or bile acid levels.

Other drugs used in the past include activated charcoal, guar gum and cholestyramine. There is very little evidence that any of these drugs have beneficial effects on the itch, liver blood tests or bile acid levels, and they are therefore rarely used.

Homeopathy does not contain active ingredients, despite its practitioners’ claims. There is no evidence-based research to support its use. As such, ICP Support does not support its use to treat ICP.

Some women have tried complementary medicines such as milk thistle and dandelion. None of these remedies has been formally tested in ICP pregnancies. However, because these remedies contain active ingredients it is important that you discuss this with your doctor.

Other things that women have found useful in the past include:

Topical treatments such as calamine lotion and aqueous cream with menthol may help to relieve the itch, although the effect may be short-lived.

Lower fat diets (but not ‘no fat’)

Healthy eating

Rest

Cool clothing

Relaxation or meditation

Counselling

Women are generally advised to avoid alcohol in pregnancy, and although it has no direct effect on ICP, this is a sensible approach.

It should be noted that none of these interventions are proven to protect your baby against the small risk of stillbirth.

Your baby may have to be delivered early.

ICP is associated with an increased risk of premature birth. This may be because your body goes into labour early, in which case it is called a spontaneous preterm birth (UDCA may help to reduce this risk), or because your doctors decide to deliver your baby early, called iatrogenic preterm birth.

Your doctor may recommend that your baby is born earlier because the risk of continuing the pregnancy outweighs the risks associated with being born early. In ICP the specific risk that doctors worry about when making the recommendation for earlier birth is the risk of stillbirth.

Because of the risk of stillbirth, most women with ICP have been giving birth to their babies early. Induction has typically been recommended at around 37–38 weeks of pregnancy, but research published in 2019 suggests that around 90 per cent of women will be able to delay induction until 39 weeks of pregnancy. However, some women with severe ICP (bile acid concentrations of ≥100 µmol/L) may need to meet their babies from 34–35 weeks of pregnancy onward. It is essential that bile acids are tested frequently in ICP to ensure that women whose levels may rise above 100 µmol/L are identified, and that the results of these tests are received quickly.

As you can see, the decision about when you should meet your baby is not an easy one to make. We therefore suggest that you talk to your doctor about what is best for you and your baby, taking into account what is known from current research.

References

Girling J, Knight CL, Chappell L; on behalf of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. BJOG 2022; 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.17206.

Ovadia C, Seed PT, Sklavounos A, Geenes V, Di Illio C, Chambers J et al. Association of adverse perinatal outcomes of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy with biochemical markers: results of aggregate and individual patient data meta-analyses. The Lancet 2019; https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31877-4.

Ovadia C, Sajous J, Seed PT, Patel K, Williamson NJ, Attilakos G, Azzaroli F, Bacq Y, Batsry L, Broom K, Brun-Furrer R, Bull L, Chambers J, Cui Y, Ding M, Dixon PH, Estiù MC, Gardiner FW, Geenes V, Grymowicz M, Günaydin B, Hague WM, Haslinger C, Hu Y, Indraccolo U, Juusela A, Kane SC, Kebapcilar A, Kebapcilar L, Kohari K, Kondrackienė J, Koster MPH, Lee RH, Liu X, Locatelli A, Macias RIR, Madazli R, Majewska A, Maksym K, Marathe JA, Morton A, Oudijk MA, Öztekin D, Peek MJ, Shennan AH, Tribe RM, Tripodi V, Özterlemez NT, Vasavan T, Audris Wong LF, Yinon Y, Zhang Q, Zloto K, Marschall H-U, Thornton J, Chappell LC, Williamson C. Ursodeoxycholic acid in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2021; Online 26 April. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00074-1.

Fetal movement monitoring

Ovadia C, Williamson C. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: recent advances. Clin Dermatol 2016; 34: 327–34.

Williamson C, Geenes V Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2014; 124: 120–33. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000346.

Next > Risks

< Back to Diagnosis

<< Back to Summary