Causes

ICP is a complex condition caused through a combination of:

hormones

genetics

environment

These all interact with each other in ways that we don’t fully understand. The information that we present is based on the most up-to-date scientific evidence that we have, but it may (and probably will) change as more research is carried out and we learn more about the condition.

-

In all pregnancies the levels of the hormones estrogen and progesterone in the blood increase. Like many substances, they are metabolised (broken down) by the liver.

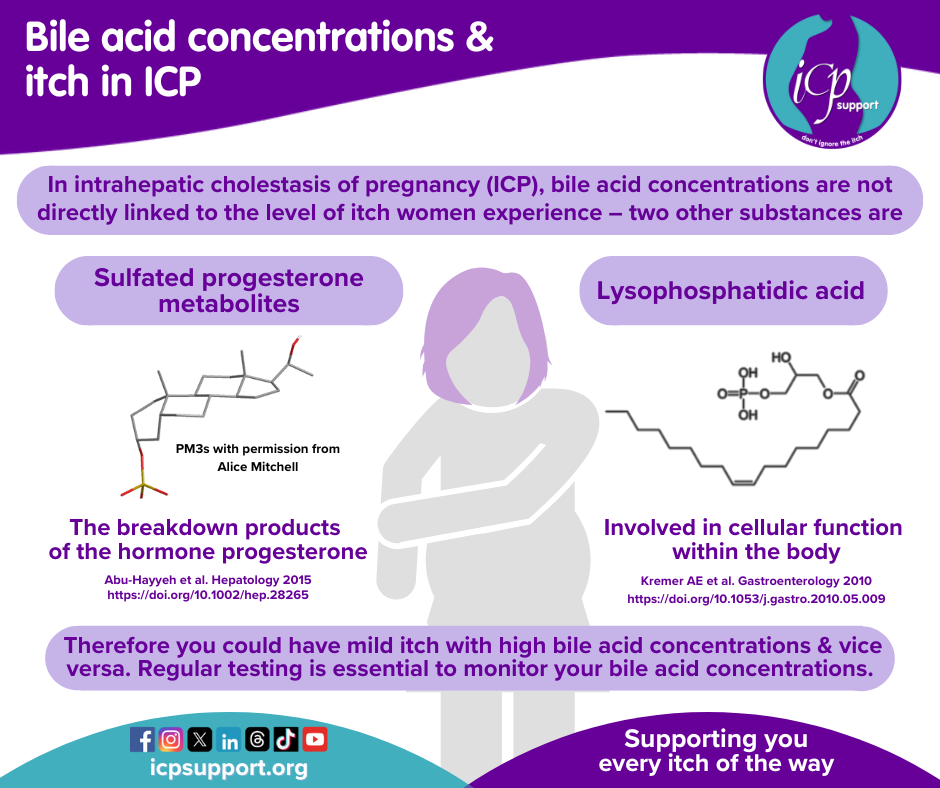

In ICP the levels of estrogen and progesterone are not higher than normal, but the level of some progesterone breakdown products (called sulfated metabolites) is higher in women with ICP. Some researchers think that it is these substances that affect the liver’s ability to cope with bile acids, leading to cholestasis. Similarly, experimental studies of high estrogen levels show that they affect the transportation of bile salts across liver cells. These theories are supported by the observation that ICP is more common in twin and triplet pregnancies, where the levels of estrogen and progesterone are naturally higher.

Women with ICP have also reported developing cholestasis following the use of oral contraceptives, and we know that progesterone preparations used to prevent preterm labour may also increase the risk of developing ICP. This does not mean that you should never be prescribed progesterone in pregnancy if the benefits outweigh the risks, however. This could either be to prevent preterm labour or as a treatment to maintain pregnancy after IVF.

Women with ICP are usually advised to avoid the combined oral contraceptive pill (which contains both estrogen and progesterone). However, contraception may be used on a ‘try and see’ basis if you feel that you have no other acceptable alternative. You must not start this until you have normal liver blood test results and your bile acids are at normal levels. You will need to let your doctor know if the pruritus (itching) returns so that a decision can be made about whether you can continue with the contraception you are using. We know that some women can tolerate the combined oral contraceptive pill, but others have reported problems on the progesterone-only pill. Why this happens is not fully understood. However, most progesterone-only contraception does not commonly cause problems in women with previous ICP. There has been little research in this area, so the long-term implications of using hormones as contraceptives are not known, so it’s important that you know this before making a decision.

-

ICP is more common in certain populations, including women of South American, Indian and Pakistani origin, and it can also run in families. How we inherit susceptibility to ICP is very complex.

Genes are passed down to us by our biological parents. It may help if you think of genes as many sets of chemical codes that are stored in a large molecule called deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and which act as the instructions, or the blueprint, for how to make a living thing. We inherit half of our genes, carried on chromosomes, from one parent and half from the other, and they can determine things like the colour of our eyes, the colour of our hair, whether we can roll our tongues and what colour our skin is. These characteristics are known as traits or phenotypes.

Sometimes the code within different genes doesn’t get copied exactly as it should. This means that the instructions are now slightly different. A simple, harmless change of coding (called a variant or a ‘polymorphism’) explains why we have traits like hair colour differences. But sometimes the changes in coding may result in more serious things, such as the condition cystic fibrosis (CF). In CF, scientists can show that this change has only happened at a single point in the coding of one gene.

In ICP, scientists have shown that rare changes in the code of two genes can be found in women with the disease. These two genes, ABCB4 (changes in about 20% of women) and ABCB11 (about 5% of women), have rare mutations that are believed to be causative - making sense, as both genes are involved in making the genes that transport bile. However, ICP is more complex - thanks to a UK wide collaboration involving the NIHR Bioresource, we also know that other types of genetic changes (common variation) are involved in ICP - they don’t directly cause the disease but can alter the risk of getting the disease 2-5x. Each of us has a different combination of these common variants, making understanding how they are involved in ICP quite complex.

Studies in this field are ongoing so stay tuned for more news in the next couple of years.

We have previously mentioned that we inherit our genes from both of our parents, so It’s possible that the genetic variant for ICP can be passed down by the father as well as the mother. If you’re trying to understand how you may have inherited this susceptibility to the condition, you need to ask both your parents (if that’s possible) about their own family history.

-

Environmental factors are thought to play a role in the development of the condition because ICP is more common in the winter months in some countries. There has been very little research conducted into the possible reasons for this variation, and at present it can’t be fully explained. Some theories include that the cause of ICP could be linked to:

Sunlight and vitamin D levels, as research studies have shown that supplementation with vitamin D can improve cholestasis in animals

Diet, as people often have a tendency to eat fattier foods in the winter

Low levels of the element selenium. More research needs to be done to investigate this.

We are asked about diet all the time. To date there is no research that suggests a particular food type to avoid or to eat more of. It makes sense to avoid, or cut down on, saturated fats such as cakes, crisps and chocolate, so healthy eating is probably the best advice we can give you. Your liver will certainly appreciate it! You may see diets advocating eating certain coloured foods or drinking lots of warm water with lemon. There isn’t any evidence that following these recommendations will harm you (although it is possible to drink too much water, believe it or not), but please still take any medications that you have been prescribed by your doctor. There is research to show that drugs like ursodeoxycholic acid can help some women, but no research to show that following specific diets will help or cure ICP. We very much hope that this will change in time. When and if research does uncover a diet that can really help we will be the first to let you know.

Some women are diagnosed with ICP following a course of penicillin-based antibiotics. Although the exact nature of the link between infection, antibiotics and ICP is not clear, research has identified a common genetic change in both women with ICP and women with drug- (antibiotic-) induced cholestasis. Whilst this does not mean that the antibiotics cause ICP, they may increase the woman’s chances of developing the condition. This is another of the small genetic changes that we refer to.

Bile acids

As we have previously mentioned, ICP is associated with potential problems for your unborn baby. It has always been suggested that the most likely cause of stillbirth comes from bile acids, and the most recent research from Ovadia (2019) has identified the level at which bile acids become a problem for the unborn baby in ICP. But what are bile acids and why are they a problem?

What are bile acids?

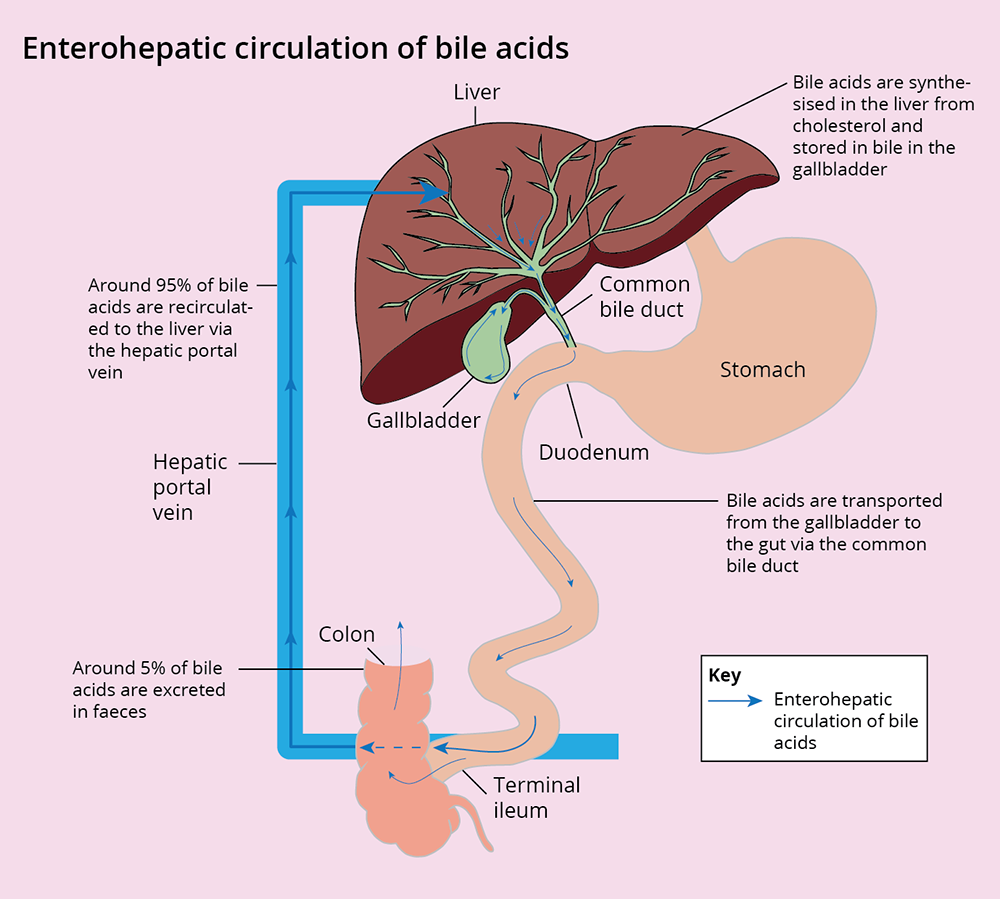

Bile acids are made (synthesised) from cholesterol in the liver. They start life as primary bile acids and in a further process (conjugation) they are converted into bile salts, which is why some doctors will call them bile salts and others will refer to them as bile acids. They are then transported from the liver into the gallbladder in bile.

Bile acids are essential, as they help the body digest food and absorb the fat-soluble vitamins we need for our bodies. During a meal, the gallbladder contracts and deposits bile into the gut (if you have had your gallbladder removed, bile will be secreted directly to the gut). Once there, and with the help of bacteria in the gut, the bile acids are turned into secondary and tertiary bile acids, including UDCA. They are then recycled, and around 95% of them are transported back to the liver via the hepatic portal vein. The remaining bile acids/salts are excreted in the faeces (poo). This entire process is called the enterohepatic circulation.

In ICP there is no evidence that individual bile acids need to be measured, so most laboratories will perform a total bile acid measurement, which includes both bile acids and salts.

What happens to bile acids in ICP?

In ICP the transport of bile acids across the liver doesn’t happen as efficiently as it should. The bile acids accumulate in the liver and eventually leak back into the blood, causing raised levels in the blood. Doctors refer to this as being ‘cholestatic’.

Because the bile acids are quite toxic it is important to try to reduce the levels. They are not thought to be harmful to you during an ICP pregnancy because they are only raised for a limited amount of time, but they may be the reason why some babies have been born prematurely or stillborn. As previously discussed, exactly how bile acids are involved is still not fully understood. Some studies have investigated their effect on the placenta and other studies have looked at their possible effect on the baby’s heart. Further research is needed to identify whether either or both of these factors are implicated in the risk to the baby, and it is important that this research continues. For the moment, researchers advocate a cautious approach to managing the condition.

Bile acids have their own circadian rhythm, which means that they naturally rise and fall (within normal reference ranges) over a 24-hour period. The time of day at which you have your blood taken to measure your bile acids can make a difference to your result, and any increase (within normal reference ranges) doesn’t mean that your bile acids are going to become abnormal or are rising – it could simply be that you have had them tested at a time of day when they are generally a little higher. They also rise after eating, but there is no evidence to suggest that you need to fast for the test – in fact, based on recent research published in The Lancet, which shows that bile acids ≥100 µmol/L are linked to an increased risk of stillbirth, it is clear that it is vital to know what they are after eating so that you can know how high they can become (peak bile acids).

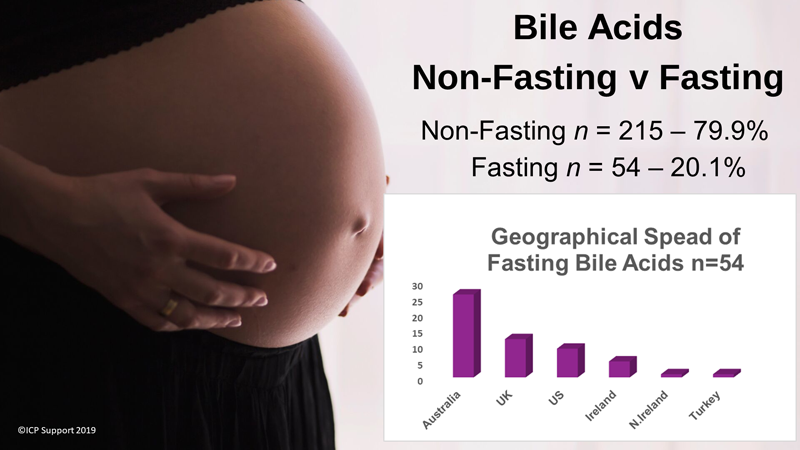

However, we are aware that many women are now being asked to fast even though there is no evidence to do so and we wanted to get an idea of how many women might be affected. We surveyed just over 260 women and the following chart gives us an idea of how many women are being asked to fast and where in the world this practice is most common. Our message to you is: don’t fast, and if told to, ask for the evidence!

Since our survey, more research has been published by Mitchell et al (2021) showing the importance of not fasting and also suggesting that the threshold for diagnosing ICP should be increased to ≥19 µmol/L.

The revised RCOG Guideline on ICP (published August 2022) does not advise fasting for bile acid samples.

Whilst this research identified that the greatest peak in bile acids was at an hour after lunch, we know that it simply isn’t practical for women to organise their bile acid tests for a set time. However, if you are being tested for ICP or you have already been diagnosed with the condition, it makes sense to be consistent about the time of day you have your test and what you have eaten beforehand. By doing this you will know that your results have not been affected by testing at different times or by eating different food. Experts in ICP also recommend that you leave around 30–120 minutes after eating before being tested, as levels will have peaked by then.

References

Hormones

Abu-Hayyeh S, Papacleovoulou G, Lovgren-Sandblom A, Tahir M, Oduwole O, Jamaludin NA, Ravat S, Nikolova V, Chambers J, Selden C, Rees M, Marschall H-U, Parker MG, Williamson C. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy levels of sulfated progesterone metabolites inhibit farnesoid X receptor resulting in a cholestatic phenotype. Hepatology 2013; 57: 716–26.

Abu-Hayyeh S, Martinez-Becerra P, Sheikh Abdul Kadir S, Selden C, Romero M, Rees M, Marschall HU, Marin JJ, Williamson C. Inhibition of Na+-taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide-mediated bile acid transport by cholestatic sulfated progesterone metabolites. J Biol Chem 2010; 285 16504–12.

Abu-Hayyeh S et al. Prognostic and mechanistic potential of progesterone sulfates in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and pruritus gravidarum Hepatology; 2015 https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.28265 (epub ahead of print)

Song X et al. Transcriptional dynamics of bile salt export pump during pregnancy: mechanisms and implications in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Hepatology; 2014 60(6): 1993–2007

Genes

Dixon PH, Williamson C. The pathophysiology of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2016; 40(2): 141–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinre.2015.12.008

Dixon PH et al. Heterozygous MDR3 missense mutation associated with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: evidence for a defect in protein trafficking. Hum Mol Genet 2000; 9: 1209–1217

Dixon PH et al. A comprehensive analysis of common genetic variation around six candidate loci for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109(1):76–84. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2013.406

Dixon PH, Sambrotta M, Chambers J, Taylor-Harris P, Syngelaki A, Nicolaides K, Knisely AS, Thompson RJ, Williamson, C. An expanded role for heterozygous mutations of ABCB4, ABCB11, ATP8B1, ABCC2 and TJP2 in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 11823; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11626-x.

Environment

Reyes H et al. Selenium, zinc and copper plasma levels in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, in normal pregnancies and in healthy individuals, in Chile. J Hepatol 2000; 32: 542–549

Wikström Shemer, Marschall HU. Decreased 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D levels in women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2010; 89: 1420–3.

Ovadia C, Williamson C. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: recent advances. Clin Dermatol 2016; 34: 327–34.

Bile acids

Girling J, Knight CL, Chappell L; on behalf of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. BJOG 2022; 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.17206.

Gao H, Chen L-J, Luo Q-Q, Liu X-X, Huu Y, Yu L-L, Zou L. Effect of cholic acid on fetal cardiac myocytes in intrahepatic choliestasis [sic] of pregnancy J Huazhong Univ Sci Technol [Med Sci] 2014; 34(5): 736–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11596-014-1344-7.

Glantz A, Marschall HU, Mattsson LA. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: Relationships between bile acid levels and fetal complication rates. Hepatology 2004; 40: 467–74. https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.20336.

Mitchell A, Ovadia C, Syngelaki A, Souretis K, Martineau M, Girling J, Vasavan, T, Fan HM, Seed PT, Chambers J, Walters JRF, Nicolaides K, Williamson C. Re-evaluating diagnostic thresholds for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: case-control and cohort study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2021; https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16669

McIlvride S, Dixon PH, Williamson C. Bile acids and gestation. Molecular Aspects of Medicine 2017; 56: 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mam.2017.05.003.

Vasavan T, Ferraro E, Ibrahim E, Dixon P, Gorelik J, Williamson C. Heart and bile acids – Clinical consequences of altered bile acid metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta 2018; 1864(4 Pt B): 1345–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.12.039.

Vasavan T, Deepak S, Jayawardane I A, Lucchini M, Martin C, Geenes V, Yang J, Lövgren-Sandblom A, Seed P T, Chambers J, Stone S, Kurlak L, Dixon P H, Marschall H-U, Gorelik J, Chappell L, Loughna P, Thornton J, Pipkin F B, Hayes-Gill B, Fifer W P, Williamson C. Fetal cardiac dysfunction in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy is associated with elevated serum bile acid concentrations. J Hepatol 2020; 74(5): 1087–1096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2020.11.038.

Next > Diagnosis

< Back to Symptoms

<< Back to Summary